@include "lib.awk"

@include "sdiscrete.awk"

"""

Simple Rule Generation (with `bore`)

------------------------------------

`Bore` is an ultra-simple rule generator for generating ultra-simple

rules. Why am I `bore`-ing you about `bore`?

Machine learners generate modes. Sometimes, people read those models.

What kind of learners generate the kind of models that people want to

read?

Before answering that, consider the plight of the modern business

manager. For 21st-century businesses, the problem is not accessing

data but ignoring irrelevant data. Most modern businesses can elec-

tronically access mountains of data such as transactions for the past

two years or the state of their assembly line. The trick is effec-

tively using the available data. In practice, this means summarizing

large data sets to find the _diamonds in the dust_ - that is, the data

that really matters.

In the data mining community, "learning the least" is an uncommon

goal. Most data miners are zealous hunters seeking detailed summaries

and generating extensive and lengthy descriptions. Here, we take a

different approach and assume that busy people don't need- or can't

use- complex models. Rather, they want only the data they need to

achieve the most benefits.

An Aside

--------

Formally, `bore` is a greedy search for rules, guided by a Bayesian

ranking heuristic. Rather than ranking features, `bore` ranks feature

ranges.

But described like that, `bore` does not seem very interesting. The

real important thing about `bore` is not the simplicity of the

algorith. Rather, it is its connection to cognitive psychology.

`Bore` is an extreme form of Occam's Razor. This is an idea first

expressed by William of Ockham (c. 1287 - 1347). It is a principle of

parsimony for problem-solving. It states that among competing

hypotheses, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected.

To put that another way:

+ Prune the unnecessary;

+ Focus on what's left.

It turns out that Occam's razor is a core principle of cognitive

psychology. In the early 1980s, Jill Larkin and her colleagues

explained human expertise in terms of a long term memory of

possibilities and a short term memory for the things we are currently

considering.

+ Expert and novice performance in solving physics problems

J Larkin, J McDermott, DP Simon, HA Simon ,

Science, Vol. 208, pp. 1335-1342.

According to Larkin et al. novices confuse themselves by overloading

their short term memory. They run so many "what if" queries that their

short term memory chokes and dies. Experts, on the other hand, only

reason about the things that matter so their short term memories have

space for conclusions. The exact details of how this is done is quite

technical, but the main lesson is clear:

+ Experts are experts since they _know what to ignore_.

Occam's razor has obvious business implications. For one thing, we can

build better decision support systems:

+ In 1916, Henri Fayol said that managers plan, organise, co-ordinate

and control. In that view, managers systematically assessing all

relevant factors to generate some optimum plan.

+ Fayol, Henri. 1916. Administration

industrielle et generale; prevoyance, organisation,

commandement, coordination, controle. H. Dunod et E. Pinat,

Paris, OCLC 40204128.

+ Then in the sixties, computers were used to automatically and

routinely generate the information needed for the Fayol model. This

was the era of the management information system (MIS), where thick

wads of paper were routninely filed in the trash can.

+ Ackoff, R. L. 1967. "Management Misinformation Systems."

Management Science (December): 319331.

+ In 1975, Mintzberg's classic empirical fly-on-the-wall tracking of

managers in the day-to-day work demonstrated that the Fayol model was

normative, rather than descriptive. For example, Mintzberg found 56

U.S. foreman who averaged 583 activities in an eight-hour shift (one

every 48 seconds). Another study of 160 British middle and top

managers found that they worked for half an hour or more without

interruption only once every two days.

+ Mintzberg, H. 1975. "The Manager's Job: Folklore and

Fact." Harvard Business Review (July August):

29-61.

The lesson of MIS is that management decision making is not inhibited

by a lack of information. Rather, according to Ackoff, it is confused

by an excess of irrelevant information. This was true in the sixties

and now, in the age of the Internet, it is doubly true. As Mitch Kapor

said in his famous quote:

+ _Getting information off the Internet is like taking a drink from a fire hydrant._

Further, the lesson of Mintzberg's study is that it is vitally

important to give managers _succinct_ summaries of their available

actions since, given their work pressures, they just cannot digest

long and overly-complex ideas. Too much data can overload a decision

maker with too many irrelevancies. Data must be condensed, before it

is useful for supporting decisions. Modern decision-support systems

evolved to filter useless information to deliver small amounts of

relevant information (a subset of all information) to the manager.

Enter Ockam's razor and `bore`

How it works

------------

`Bore` is short for "best or rest". Given two tables, it sorts feature

ranges according to their frequency in the two tables. `Bore` ranks

highest the ranges that are more common in the _better_ table.

Note that `bore` does not care how you decided which table was

_better_ (that is something you can discuss with your business users).

However it is defined, `bore` seeks some constraint that when applied

to the data in both tables, that it selects more for _better_ than for

worse.

`Bore` uses a variant of Bayes theorem to sort the ranges. For

example, in K = 10, 000 examples fall into two tables containing 1,000

examples in _best_ and 9,000 in _rest. Suppose further we were

ranking the value of requiring very high reliability; i.e. _rely =

vh_. If so, we would count how often it appears in the _best_ and

_rest_ tables. For this example, we will assume it appears 10 times

in _best_ and 5 times in _rest_. Hence, we could score this range as

follows:

E = (rely=vh)

P(best) = 1000/10000 = 0.1

freq(E|best) = 10/1000 = 0.01

freq(E|rest) = 5/9000 = 0.00056

b = like(best|E) = freq(E|best) * P(best) = 0.001

r = like(rest|E) = freq(E|rest) * P(rest) = 0.000504

P(best|E) = b/(b + r) = 0.66

Clark explored this approach and found it to be a poor ranking

heuristic when it is distracted by low frequeny evidence. For

example, note how the probability of _E_ belonging to the _best_ class

is moderately high even though its _support_ is very low; i.e. _P

(best|E) = 0.66_ but _freq(E|best) = 0.01_.

+ _R. Clark. Faster treatment learning, Computer Science, Portland State University. Master's thesis, 2005_

To avoid such unreliable low frequency evidence, Clark augmented the

above with a support term. Support should increase as the frequency

of a range increases, i.e. _like(best|x)_ is a valid support measure.

Hence `bore` ranks ranges via

P(best|E) * support(best|E) = b^2 / (b+r)

This simple equation has some interesting properties. The range of _b_

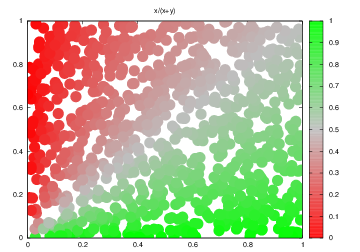

and _r_ are zero to one. Here's _ b / (b+r)_. Note how this function

can reward ranges, even if they are very uncommon in _b_:

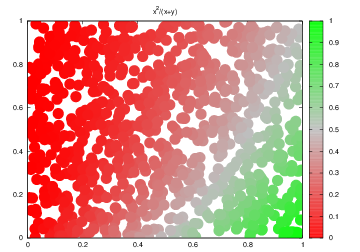

And here's _b^2 / (b+r)_. Note that this measure offers enthusiastic

support for only the ranges that are frequent in _b_.

Code

----

### Main Driver

Note that this main driver divided numerics into _bins=7_.

Here's an example main driver for `bore`:

+ It defines _better_ to be the class _tested negative_ in the file _data/diabetes.csv_ (so the goal here is to find the

things that selects for patients that are more _negative_ (i.e. not sick) than _positive_ (i.e. sick).

+ It reads some data from disk into a take (see `readcsv`);

+ It discretizes the numerics (see `sdiscrete`):

+ How the data is discretized is a lower-level detail that we need obsess on at this time.

+ For the record, we use `bins=7` and ignore any

division whose `max - min` is less than `tiny=0.3` times the standard deviation for that column.

+ But you could use something else.

+ It then ranks the discretized ranges use the `bore` function.

+ It then tests that ranking using the `forwardSelect` described below.

Code follows:

"""

function _bore( _Table, f,t1,bins,tiny,

want,_Tables,t,out,enough,some,best,m,good,skip) {

f="data/diabetes.csv";

bins = 7; tiny=0.3; enough=0.25; want="tested_negative"

readcsv(f,0,_Table)

t1 = sdiscrete(_Table, 0, bins, tiny)

tables(_Table[t1],_Tables)

m=bore(_Tables,names,want,enough,good,skip)

o(colnum[t1],"nums")

o(good,"good")

forwardSelect(length(datas[want]),-1,1,m,

names,want,good,_Tables,best)

o(best,"best")

}

"""

### Range Ranking with `bore`

Note that in the following, we employ a couple of search biases:

+ The following two rules come from the geometry of _b^2 / (b+r)_ space (shown above):

+ *Rule1*: Only consider ranges with _b > r_;

+ *Rule2*: Only consider ranges with _b>0.5_;

+ *Rule3*: Ignore all ranges with a score less than _enough*max(score)_ (in this code, _enough=25%);

"""

function bore(_Tables,all,want,enough,out,skip,

t,yes,no,best,rest,x,y,b,r,tmp,max,inc,m,items) {

for(t in all) {

items = length(datas[t])

t == want ? best += items : rest += items

for(x in indeps[t])

if(! (x in skip))

for(y in counts[t][x]) {

inc = counts[t][x][y]

t == want ? yes[x][y] += inc : no[x][y] += inc

}}

for(x in yes)

for(y in yes[x]) {

b = yes[x][y]/ best

r = no[ x][y]/ rest

if (b > r && b > 0.5) { # rule1 and rule2

m++

out[m]["x"] = x

out[m]["y"] = y

out[m]["z"] = tmp = b^2/(b+r)

if (tmp > max) max=tmp

}}

for(m in out)

if (out[m]["z"] < enough*max) # rule3

delete out[m]

return asort(out,out,"zsortdown")

}

"""

### Checking Ranges with `forwardSelect`

While the _bore_ heuristic can suggest what _might_ be useful, it

is important to check those suggestions with a _forward select_.

+ Take the ranges, sorted by the _b^2/(b+r)

+ Find the rows selected by the top _x_ items in that sort.

+ Score those rows.

+ Let _best_ be the rows with the _want_ed class

+ Let _rest_ be the rest

+ Let score be _best/(best + rest)_

+ Note some termination rules:

+ *Rule1*: Give up if _enough_ of the _best_ (here , _enough_ = 33%);

+ *Rule2*: Give up if the top _x_ items do not better than the top _x-1_ items;

+ *Rule3*: Give up if we run out of good ranges

this If they contain the _wanted_ class, then _best++_.

+ Recurse on the se

+ Find the rows selected by the top _x+1_ items.

+ If the

"""

function forwardSelect(seen,b4,lo,hi,all,want,good,_Tables,out,support,

t,m,total,score,some,tmp,best,rest) {

support = support ? support : 0.33

support = support * length(datas[want])

if (lo > hi) return somes(good,lo-1,out) # Rule3

if (seen < support) return somes(good,lo-1,out) # Rule1

somes(good,lo,some)

for(t in all) { # for `all` the tables we are examining

tmp = rowsWith(some,_Tables[t])

t == want ? best += tmp : rest += tmp

}

score = best/(best+rest)

print "Got", best,int(100*score),"%"

if (best > support && score > b4) # Rule1, Rule2

return forwardSelect(best,score,lo+1,hi,all,want,good,_Tables,out)

else

return somes(good,lo-1,out)

}

"""

Not shown here is `rowsWith`. This is function that takes

a list of the top _x_ ranges and finds the right rows.

Here's the relevant code, copied from

[tables.awk](https://github.com/timm/auk/blob/master/src/table.auk):

In this code `this` contains the top _x_ items.

The `rowsWith` function finds all the rows that match to the `this`.

function rowsWith(this,_Table, out, d) {

for(d in data)

if (rowHas(this,data[d]))

out[d]

return length(out)

}

This code uses `rowHas` to match to one specific row.

Note that `rowHas` has to handle conjunctions and disjunctions.

So:

+ *Rule1*: for each column mentioned in `this`, there must be

at least of those ranges in the row.

Note that this rule handles disjunctions and conjunctions in a uniform

manner.

+ If `this` reference some column multiple times, we must find

its range at least once.

+ And if `this` only mentions one range for a column, then

it still works.

Code:

function rowHas(this,row, col,val,has) {

for(col in this) {

for(val in this[col])

if (row[col]== val)

has[col]++

if (has[col]<1) return 0 # Rule1

}

return 1

}

### Low-level Detail: Select `some`

Here's a small function that explores `all` known ranges, then returns

just `some` (specifically, only up to the first `max` items in `all`).

"""

function somes(all,max,some, i,x,y) {

for(i=1;i<=max;i++) {

x = all[i]["x"]

y = all[i]["y"]

some[x][y]

}}

"""

## Results

Now that all that is working, lets see some output on

[data/diabtes.csv](https://github.com/timm/auk/blob/master/data/diabetes.csv).

In this example, the column names are numbered as follows:

nums[age] = (8)

nums[insu] = (5)

nums[mass] = (6)

nums[pedi] = (7)

nums[plas] = (2)

nums[preg] = (1)

nums[pres] = (3)

nums[skin] = (4)

### Ranges Ranked with `Bore`

Here is what `bore` things are promising ranges, ranked according

to their `bore` score (shown here as `z`).

The first entry is about column five (insu: use of insulin).

Note that `bore` has decided that _<=120.857_ is the best predictor

for _testedNegative_.

good[1]

| [x] = (5)

| [y] = (<=120.857)

| [z] = (0.450894)

good[2]

| [x] = (7)

| [y] = (<=0.669143)

| [z] = (0.450441)

good[3]

| [x] = (8)

| [y] = (<=34.2857)

| [z] = (0.438954)

good[4]

| [x] = (1)

| [y] = (<=2.42857)

| [z] = (0.326694)

Exercise for the reader: why are there only four entries in this list?

Surely there are many more ranges in _diabestes.csv_?

### Ranges Selected by `forwardSelect`:

`ForwardSelect` tried the first one, the two, then three,

then four items in the above list. It found that the first

three were as good with anything else.

best[5]

| [<=120.857] = ()

best[7]

| [<=0.669143] = ()

best[8]

| [<=34.2857] = ()

To read the above, recall that

+ Column 8 = age

+ Column 5 = insu (use of insulin)

+ Column 7 = pedi (the diabtes pedigree function). The Diabetes

Pedigree Function (DPF) was developed by Smith, et al. [4] to

provide a synthesis of the diabetes mellitus history in relatives

and the genetic relationship of those relatives to the subject. The

DPF uses information from parents, grandparents, siblings, aunts and

uncles, and first cousins. It provides a measure of the expected

genetic influence of affected and unaffected relatives on the

subject’s eventual diabetes risk.

+ J. W. Smith, J. E. Everhart, W. C. Dickson, W. C. Knowler,

and R. S. Johannes (1988). Using the ADAP learning algorithm to

forecast the onset of diabetes mellitus. InSymposium on Computer

Applications in Medical Care, 261–265.

## Discussion

The result above is interesting: out of all that data, there is

only a few ranges that most predict for (say) not having diabetes.

This is a repeated result with `bore`. If features are discretized

and then ranked by `b^2/(b+r)` and we ignore all ranges the _b < r_

or _b < 0.5_, we end up with very small rule bases. This suggests

that either `bore` is missing details OR that the underlying

model in these data sets is very simple.

In support of the latter idea (that the underlying structures in many

data sets are very simple), I offer the follow range ranking result

using a completely different method. In this approach, the

wider the horizontal line, the more a range can select for different

classes (to the left selects for defective software classes

and to the right selects for non-defective). Also, the closer

the ranges to the vertical line, the less useful they are for

selecting for any class. Note that most of the ranges are very

narrow and fall close to the vertical line; i.e. only a very small

subset of these ranges matter at all.

I show the above, not because I endorse that particular analysis

(it does not have a `forwardSelect` so it can offer overly enthusiastic

support for things that do not actually work). But rather,

I show it to illustrate that the methods of many researchers report

that when doing range selection, only a few things matter.

Coming back to the start of this lecture- note how we can now

offer automatic support for

+ Prune the unnecessary

+ Focus on what's left.

(By the way, if you want to know how that last diagram was generated,

see

+ [Nomograms for Visualization of Naive Bayesian Classifier](http://iccle.googlecode.com/svn/trunk/share/pdf/mozina04.pdf).

M. Mozina and J. Demsar and M. Kattan and B. Zupa,

Proceedings PKDD'04, 2004)

### Cautionary Note

Of course, not all domains are so simple as to allow the extraction

of ultra-simple rules. I'm often asked "how to check if this approach

is too simple?". My reply is "try it" using a cross-val experiment.

All the above code runs in near-linear time:

+ If the resulting rules

work then you have an ultra-simple solution.

+ And if they don't, then at least you'll have some a simple

baseline result against which you can document the power of

your favorite, more sophisticated technique.

"""